There are many advantages to using validated instruments while evaluating a family communication system. First, we can claim that the questions we ask actually measure what we think they measure. Second, if multiple studies use the same instrument, new forms of analysis become possible — allowing us to better build on each other’s work and conduct meta-analyses. Third, using validated instruments allows us to have better conversations outside of our immediate field. There are a number of validated instruments out there that may be useful and I want to highlight a few here. Other instruments that researchers in this domain have found relevant that have been listed on the Designing for Families wiki and that’s a good place to add to if you know of something good.

When evaluating communication technology, you may want to make claims about its effect on various aspects of the relationship between the people it is meant to connect. I suggest using the Network of Relationships Inventory (NRI) or Social Connectedness Questionnaire (specific version) in this case. If the relationship you are measuring is of a specific type (e.g. parent and child, married couple), it may also make sense to use a more targeted validated measure such as the Parent-Child Relationship Questionnaire. Sometimes, a technology may not be designed for a specific pair of people, but rather meant to increase a given users general sense of connectedness to others or emotional well-being. Two useful measures in this case are the Social Connectedness Questionnaire (overall version) and the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS).

All of the measures I mentioned so far measure outcomes but do not ask the participant to reflect on the technology that used. If this seems useful to you, you may want to take a look at the Affective Benefits and Costs Questionnaire (ABC-Q). I’ve been designing and validating a more focused version of it called the Affective Benefits and Costs of Communication Technologies (ABCCT) questionnaire. I have preliminary validations of versions for use with both children and adults, so feel free to try them out.

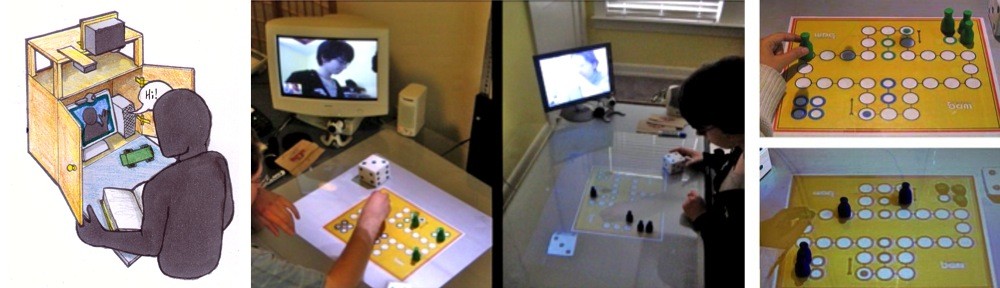

However, all of the above measures are really only useful if the person has had an opportunity to try your technology over a period of time so that changes in relationships, affect, and communication practices can be detected. However, there are a few validated measures that I find to be valid after a short interaction (such as a lab study). The Networked Minds Social Presence Measure is appropriate to use with adults. I have not had success adapting it to children as I think they may have trouble reflecting on a short interaction in this abstract fashion. With children, I’ve had more success using validated observational metrics to code video of system use, for example the Howes levels of social play coding scheme when looking at remote play.

If there is no validated measure for the aspect you are investigating, it may make sense to design and validate something that others would be able to use. I’d love to hear about this kind of work if anybody is doing it and early designs of such surveys.

All Mentioned Measures:

- Bel, D.T. van, Smolders, K.C.H.J., IJsselsteijn, W.A., and Kort, Y.A.W. de. Social connectedness : concept and measurement. International Conference on Intelligent Environments, IOS Press (2011), 67-74.

- Furman, W. and Buhrmester, D. The Network of Relationships Inventory: Behavioral Systems Version. International journal of behavioral development 33, 5 (2009), 470-478.

- Furman, W. Parent-Child Relationship Questionnaire. In J. Touliatos, B.F. Perlmutter, M.A. Straus and G.W. Holden, eds., Handbook of Family Measurement Techniques. SAGE, 2001, 285-289.

- Harms, C. and Biocca, F. Internal consistency and reliability of the networked minds social presence measure. (2004), 246.

- Howes, C., Unger, O., and Seidner, L.B. Social Pretend Play in Toddlers: Parallels with Social Play and with Solitary Pretend. Child Development Vol. 60, N. 1 (1989), 77-84.

- IJsselsteijn, W., Baren, J. Van, Markopoulos, P., Romero, N., and Ruyter, B. de. Measuring Affective Benefits and Costs of Mediated Awareness: Development and Validation of the ABC-Questionnaire. In Awareness Systems. 2009, 473-488.

- Thompson, E.R. Development and Validation of an Internationally Reliable Short-Form of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 38, 2 (2007), 227-242.

- Yarosh, S. and Markopoulos, P. Design of an instrument for the evaluation of communication technologies with children. Proc. of IDC, ACM (2010), 266–269.