As a family communication researcher, people frequently ask me for ideas on making videochat work better for their families (especially between children and grandparents). While I think there is a lot of room to make new technologies in this space, there are ways of leveraging existing technologies, too.

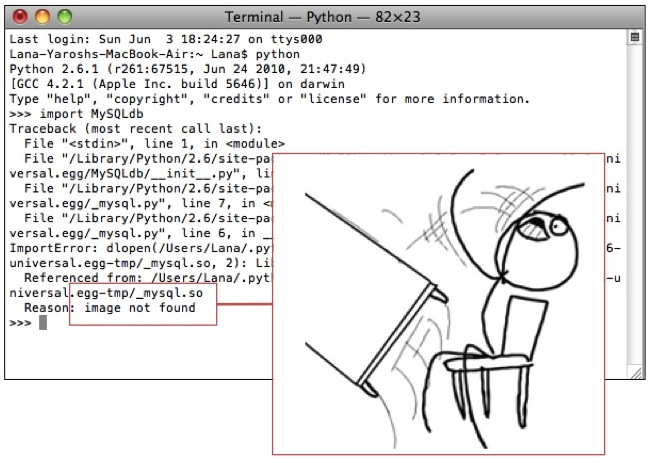

One of the big challenges for videochat is that setup can be problematic and frequently requires a tech savvy adult on each side. For example, a participant in one of my studies described his experience:

Video is nice, but getting it to work from both the ends wasn’t worth it. We’d have the phone going, and I’d be saying “hit that thing on the right” or whatever. It would take forever to get it set up. Especially with people that are not that technical. Like we tried video with grandparents and my dad is the least computer literate person I know. We literally spent and hour and a half setting up a call which lasted 5 minutes. It gets to the point when it’s not worth it. So, our main method is the phone.

One solution is installing TeamViewer on the remote machine (e.g., next time you visit). This free program gives you really easy-to-use remote access so that now you can start the call on both sides at the agreed upon time and do basic troubleshooting without having to do tech support over the phone.

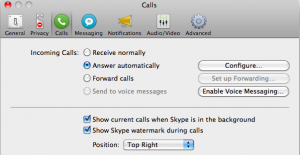

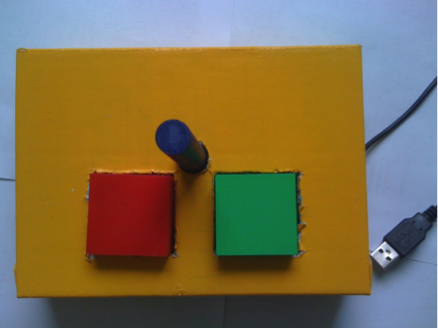

Another solution is setting up a dedicated device (such as an old laptop) at a good location in the remote participants’ home. Set Skype to start and auto-login each time the machine restarts and set incoming calls to auto-connect with video. However, the downside of this approach is that you have to use social conventions to manage availability (e.g., call first by phone and agree on a time to connect before trying to Skype).

Another problem with currently-available videochat is that it really gets boring pretty quick (this is especially true while talking to children). The key to making videochat work is coming up with compelling activities to do together, rather than just talking. There is a lot of great research in this space, as well as some existing stuff out there. So, if you’re struggling to find something to do to keep your videochat sessions more engaging, try a few of these and see if you like them:

- Story Visit from Nokia is a great free tool to read books together remotely and even gives advice to make the reading experience more engaging!

- Once you’re done with those stories, you can try to find other books online (you’ll have to coordinate the page-turning yourself, but at least you can see them easily). I suggest using the International Children’s Digital Library which has a huge collection.

- Yahoo! Multiplayer games can be a good way to stay in touch as long as you can find somebody to help set it up on the other side (or use the TeamViewer trick above). Or try Rounds, which combines videochat and games.

- If you want to try something that stretches across sessions, I would suggest trying a virtual world together, choosing one that suits your child’s age and interests. The popular ones include: Petpet Park, Club Penguin, Neopets, World of Warcraft, and Minecraft. Unfortunately, the last two are best played fullscreen, so it may reduce the communication to audio-only.

- You can use an online whiteboard (like Scriblink) to draw together synchronously, or sign up for a specialized social network like Sesame’s Streets familiesnearandfar.org to send asynchronous drawings and messages (this site was made for military families, but is open to everybody)

- Finally, sometimes it can be fun just to play with regular physical toys over videochat. Some ideas that work well include: puppet show, tea party, playing the game Battleship, showing magic tricks, and dressing up dolls for a fashion show. I’m sure you can come up with other things based on your interests.