My research depends on participants volunteering their time, energy, and personal stories. They are informants, co-designers, beta testers, and content experts who contribute so many insights and yet frequently remain anonymous in publications resulting from the work. Like many other researchers, I struggle with how I can give something back (beyond free pizza or gift cards for participation.

One of my favorite readings on the topic of “giving back” is the Le Dantec & Fox CSCW 2015 paper on community-based research, which really examined how institutions may exploit vulnerable communities (despite having the best intentions) without actually contributing back anything that is of value to the participants. University research may appear to promise things like policy and institutional change, increased access to resources, or (in the case of HCI) working technologies that address user needs. The truth is that these are almost never delivered in the form or at a time that can actually directly benefit study participants. I know for my research, I have no source of funding that would support developing and maintaining a production-quality system beyond the initial novel prototypes in constrained deployments. So is there a way to give back that doesn’t over-promise? Here are five strategies that I’ve tried in my work:

PARTNERING with an ORGANIZATION (which is willing to develop and maintain prototype ideas): If your research is done in collaboration with an existing technology company, your findings and prototypes can be directly integrated into their services without the researcher needing to coordinate long-term maintenance (in turn, the company gets a free research team and initial development of cool feature ideas). This is currently our approach in our collaboration with CaringBridge.org, as our findings are directly driving new features and directions (this work is largely in progress, but here are some publications). Obviously, these partnerships can take a lot of time and effort to set up and manage, but I really think this is a great pathway to positive impact.

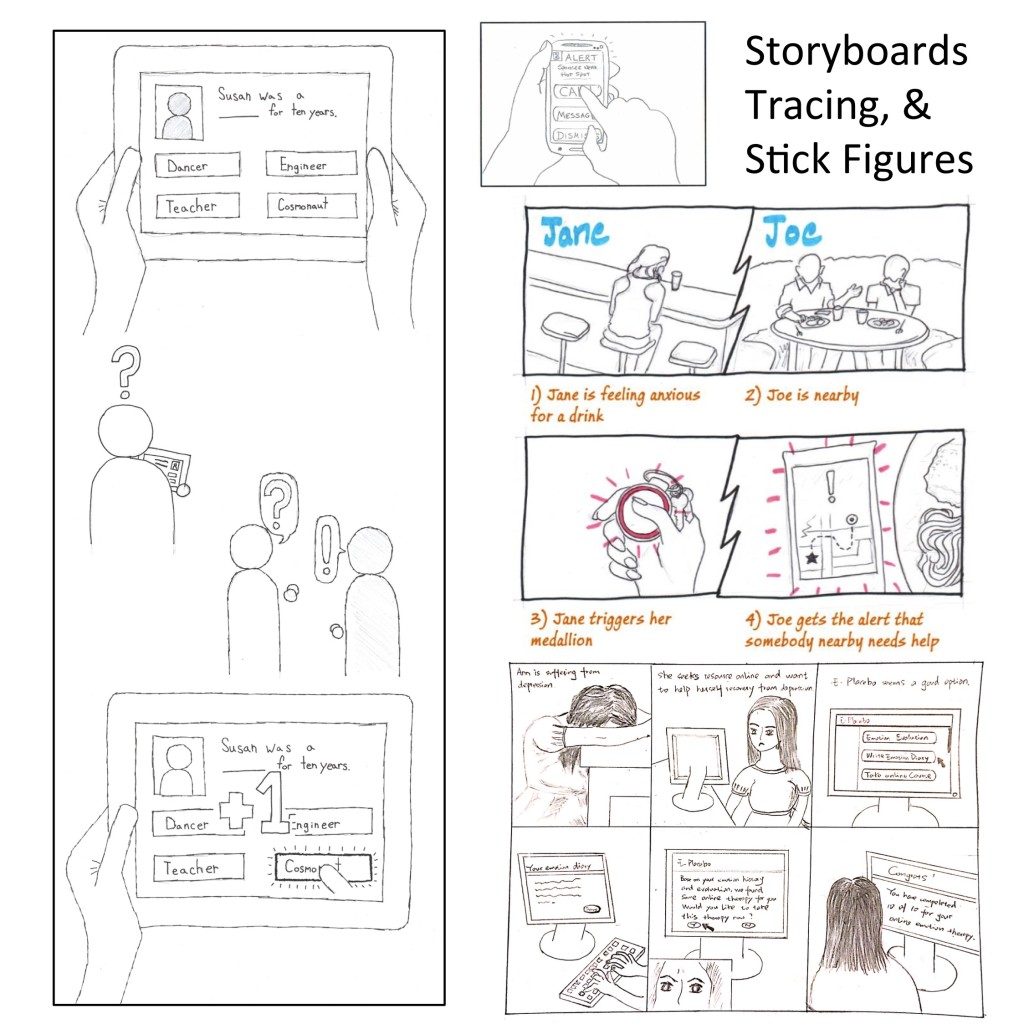

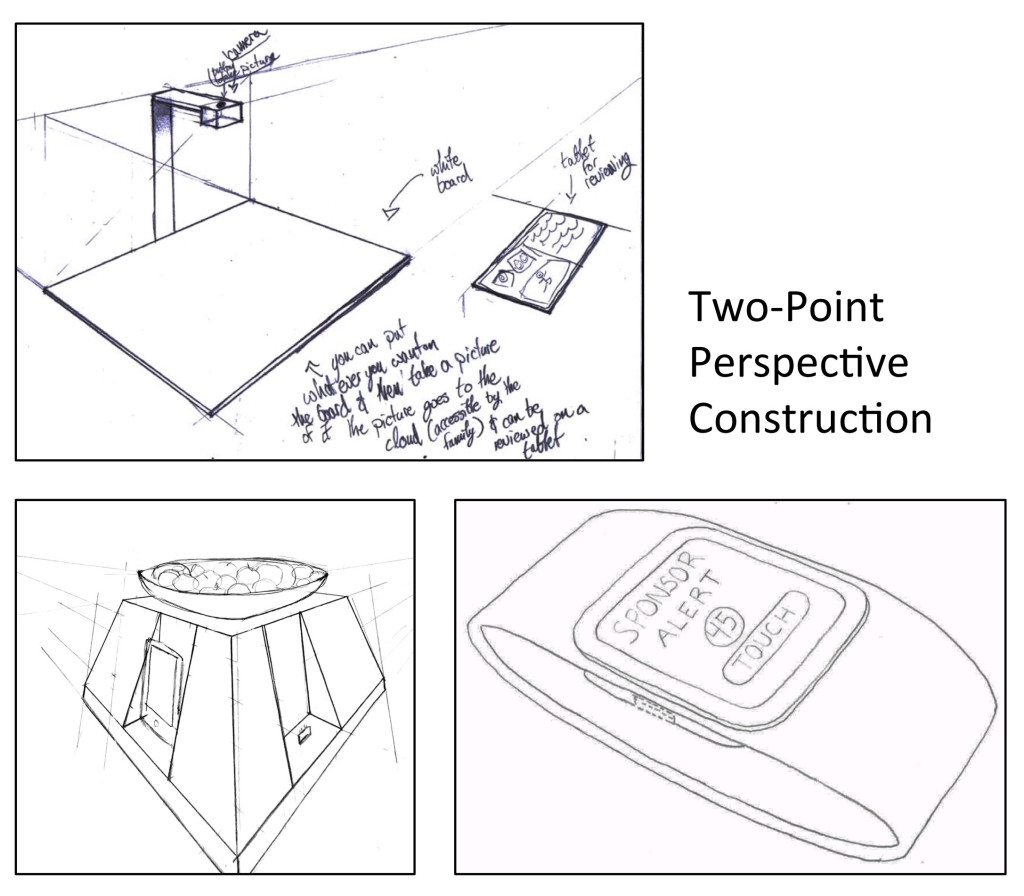

STUDY PARTICIPATION as BENEFIT: In many cases, being part of a participatory design process can tangibly benefit the co-designers. For some good reading, I love the way the KidsTeam at University of Maryland has reflected on the perceived benefits of and ethical considerations for co-design with children. It is certainly important to think about the possible benefits up-front and consider how they can be amplified and measured. If the benefits are pedagogical, this may mean thinking through the specific learning outcomes holistically and for each session. When planning my studies, I consider how being part of it may help participants identify new resources that may personally help them, develop actionable resilience skills, etc. This does typically mean that I can’t accomplish my studies as a single design workshop, instead requiring multiple sessions for the partnership to be able to yield benefits both to the researchers and to the participants.

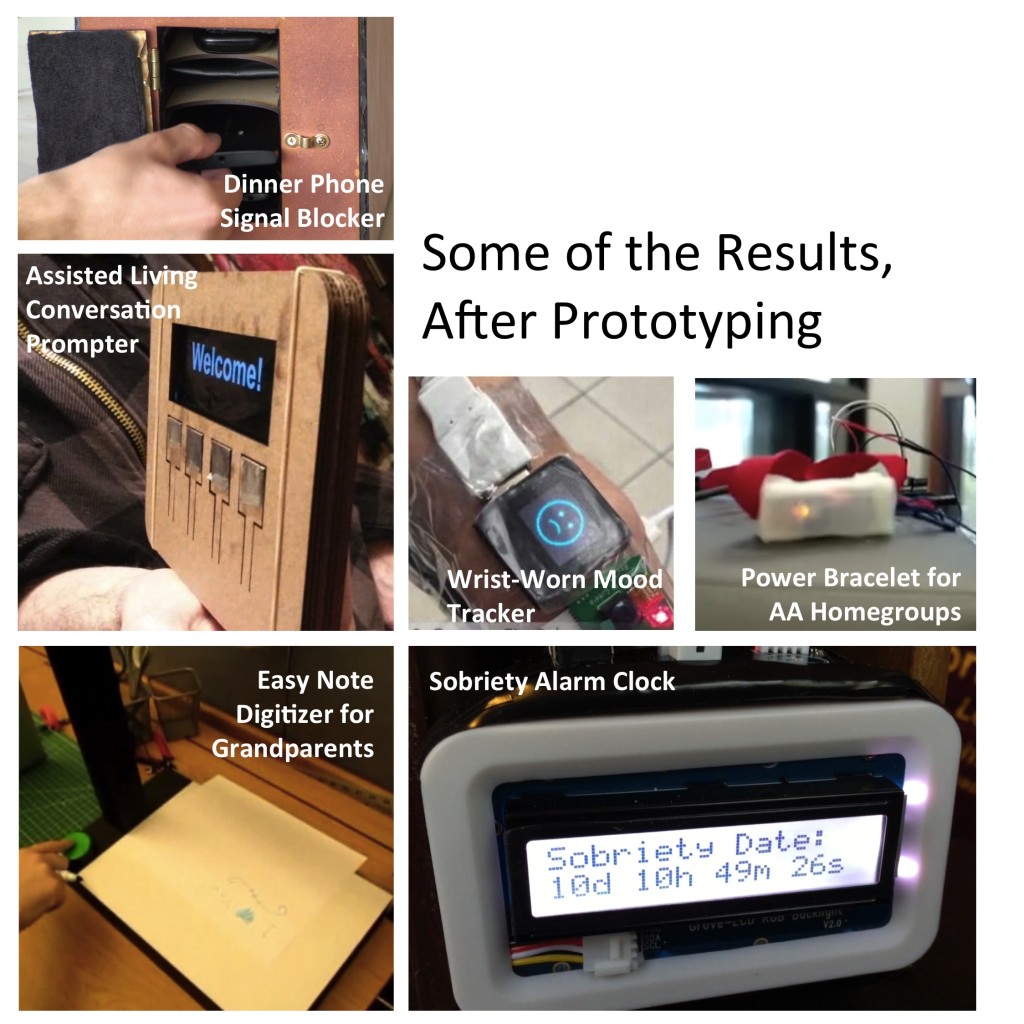

LEAVING BEHIND STOP-GAP SOLUTIONS (with currently-available technologies): While you can’t usually leave behind and maintain a fully functional prototype system, there may be great opportunities to leave behind solutions that may be better than what the family had available in the past. For example, after running a study with a novel prototype that I had to remove, I left behind dedicated smartphones set up for easy videochat (just off-the-shelf phones with Skype installed). This wasn’t as good as my prototype, but it was much better than the previous audio-only setup that the family used. This did require additional resources (in this case, phones), but it’s worth it if it leaves the participants better off than before you got there.

AUTHORSHIP or ACKNOWLEDGEMENT: This one doesn’t apply if you’re working with communities that face stigma or want to remain anonymous, but there are cases where it may be ethical to credit creators or acknowledge co-designers. We are currently working on a project with Middle School co-designers, where all contributors will be able to choose to be listed as co-authors. After all, they spent a whole year with us learning how to be designers and coming up with ideas — they should get something that they can put on their resumes for college! This does require thinking through at study-planning time so that a special check box can be included on the consent form.

DISSEMINATING INFORMATION on BEST PRACTICES (with currently-available technologies): After doing a formative study, you may be in a really good position to share best practices for specific challenges. For example, after completing my research on parent-child communication in separated families, I wrote a blog post on practices, strategies, and tools that may help families make best use of currently-available systems. I distributed this to my participants directly, but also left it online for any other families who may be looking for ideas or advice. In another example, I led a webinar for medical practitioners to understand the technologies and practices that work well for people in recovery. Since the medical practitioners are often the first “line of defense” for people in recovery, this is a great way to disseminate potentially-helpful information. The good news is that this approach is also really consistent with and rewarded by the NSF expectations for Broader Impact.

Are there practices that you’ve tried in your research that have helped you give back to your participants? I’d love to hear other ideas, because I really think this is a fundamental tension and challenge in HCI research.

Note: This blog post started as a conversation at the CSCW 2018 Workshop on “Conducting Research with Stigmatized Populations.” Stigmatized participants have greater risks from participating in research, so thinking about ways of amplifying benefit using strategies above is particularly critical. However, there is no reason why we can’t think about amplifying benefit for all populations!