Recently, I organized an invention workshop for AT&T’s “Take Our Kids to Work Day.” This involved three 45-minute workshops and almost 300 children (ages 7-15)! I’ve never designed with children on this scale and I wanted to share how it worked and some lessons from it (as well as share my materials, in case anybody would find that to be helpful).

What We Did: I gave a quick presentation on the 5 steps I take to invent, using the ShareTable as a concrete example. The kids were divided into 2 teams of 4 people at each table and each team had a different design challenge. They then had 20 minutes to come up with ideas and draw some inventions. Finally, they presented their best idea to the other team at the table, taking about 5 minutes each. I circulated throughout the rooms, focusing on the teams that were sitting back, instead of leaning forward.

What Worked:

- Doing such large groups meant that I could very quickly get an understanding of whether something was working. For example, in the first workshop there were 4 teams that had the design challenge of a system that helps a shy kid who moves to a new school. All 4 teams really struggled with this challenge, so I was able to pull it out and replace it with different challenges for the two subsequent workshops.

- Design challenges that focused on more physical ideas, like fun on car trips and taking care of pets, yielded a larger variety of ideas.

- I got names and emails of families that might be interested in trying out new technologies. This is a great solution to age-old recruitment problem!

- The prompt that worked best, directed to the whole group, was: “If you’re having trouble coming up with a good idea, write down a really bad idea. Cross it out and write the opposite of it.” See example below:

![[Bobby] was thinking about ideas for better car trips. (1) He wrote down "I can't think of anything" in the middle of the page. (2) I make the suggestion that he think of a bad idea first, he writes "something that hijacks your car." (3) I tell his to cross it out and write the opposite of it, he writes "an app to help you find your car." He sees that as a good idea, gets excited and quick comes up with and draws 3 more ideas.](https://lanayarosh.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/ATT-Presentation-Template.jpg)

[Bobby] was thinking about ideas for better car trips. (1) He wrote down “I can’t think of anything” in the middle of the page. (2) I make the suggestion that he think of a bad idea first, he writes “something that hijacks your car.” (3) I tell his to cross it out and write the opposite of it, he writes “an app to help you find your car.” He sees that as a good idea, gets excited and quickly comes up with and draws 3 more ideas.

- Very large groups meant very little one-on-one time with me. In general, the groups that I spoke to during the design session produced better ideas and were able to push past the initial “obvious” idea. Unfortunately, I couldn’t get to every team.

- It was easy for the more shy kids to sit back and not participate, since there was little hands-on supervision from adults during the design exercise.

- I was hoping to be able to do repeat sessions with kids who put down their names as being interested, however it seems that there are legal issues with having parents bring children to work outside of a formally organized event. So, it is likely that I will not be able to follow up with the children from this workshop in-person.

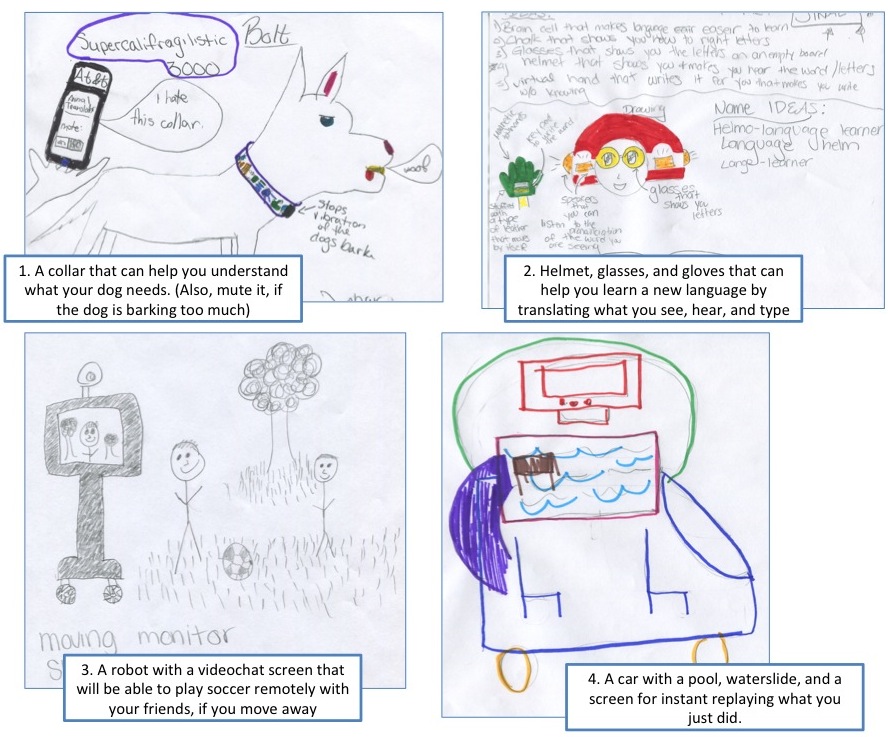

Why Do This: Designing with children is actually a great way to get ideas. Designing with a big group is great way to understand the ideas that would be valued by that culture. The kids are probably not going to come up with the next thing that you will patent, but with a little bit of translating, you can get to some interesting underlying nuggets. For example, take a look at these four ideas:

Four ideas from the workshop. These may not be directly implemented, but they can tell us a lot about designing in these domains.

Now, let me try to translate what I got out of them: (1) We may not be able to make a translator for dogs, but perhaps there could be other ways of making the invisible visible, such as displaying physiological variables. This would be interesting as a contribution to the burgeoning field of pet-computer interaction. (2) Almost every team that worked on the translating problem came up with some variations on glasses and headphones (this one also came up with a typing glove), which shows that children might be quite comfortable with wearable computing, so that’s not a bad bet for the future. (3) Most teams that worked on the remote best friends idea, came up with something that was embodied, could interact with the remote space, and could participate in play. These are all excellent ideas to include in any technology for remote contact in the home. (4) There were a lot of variations on physical activities in cars (pools, slides, trampolines, etc.). While it’s probably impractical to go off and try to make this actually happen, this points to the idea that what kids really want to be able to do in the car is something physical. Hmmm… DDR for the car? *runs off to the patent office*

So to summarize, I think there is a lot of value to be had from even one-off invention workshops with children (as long as you’re willing to do some translating of the final ideas). Regardless of where you work, you may be able to organize one of these in the context of a take your kids to work day. Even if you end up with a giant group, it’s still doable and there are even some advantages to it.